- What We Do

- Agriculture and Food Security

- Democracy, Human Rights and Governance

- Economic Growth and Trade

- Education

- Environment and Global Climate Change

- Gender Equality and Women's Empowerment

- Global Health

- Humanitarian Assistance

- Transformation at USAID

- Water and Sanitation

- Working in Crises and Conflict

- U.S. Global Development Lab

Speeches Shim

In Malawi, drones prove successful in delivering health commodities to remote areas

ABOUT THE AUTHOR: René Berger is Director of GHSC-PSM, Samantha Salcedo-Mason is Managing Director of CLEAR, Jay Heavner is Senior Knowledge Management and Communication Manager, Marie Maroun is Senior Communications Specialist, and Ryan Triche is Warehousing and Distribution Analyst with the USAID Global Health Supply Chain Program-Procurement and Supply Management project.

In Thotho, a remote village on the shores of Lake Malawi, the residents fish at night under the light of paraffin lanterns that draw the sardine-like usipa to their small wooden canoes.

Fishing is life here. As the locals say, “If you don’t fish, you don’t eat.”

Life in Thotho also relies on the health dispensary just up the hill from the lake – a two-room building stocked mainly with a small cabinet of essential medicines. Doctors and nurses visit the dispensary infrequently, but a health surveillance assistant named Baxton Kamanga says it is a lifeline for those seeking basic medical care.

Baxton arrives at the dispensary daily at 8 a.m., just a few hours after the fishermen have smoked and dried their daily catch or sold what they can. The dispensary is a 15-minute walk from Baxton’s house, but a world away from the nearest health clinics that lie along the coast – north and south of Thotho but require travel by boat to reach.

“My motive is to help…working with sick people, talking to them and telling them it will be alright,” Baxton said.

Until the summer of 2019, the only way to transport medical supplies to Thotho and several other hard-to-reach areas in Northern Malawi was by boat. There are no cars, trucks, or airports here.

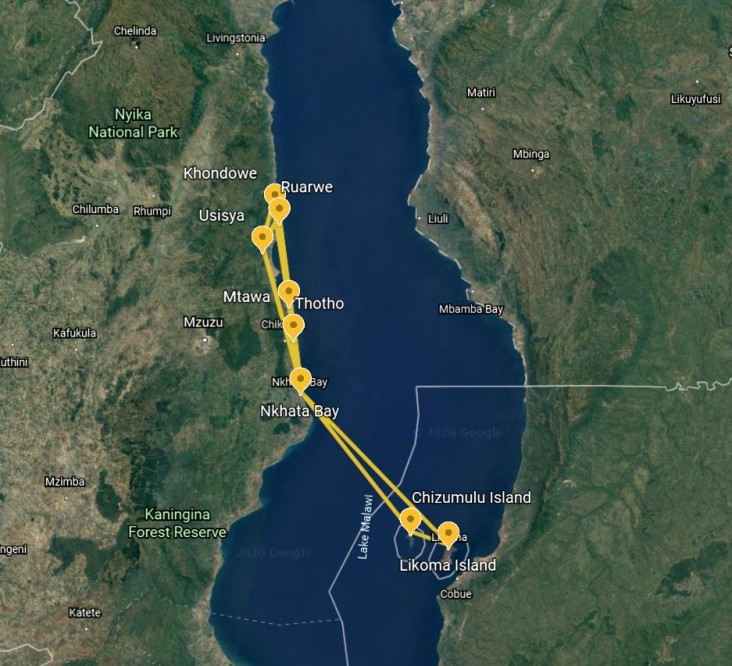

It was then that USAID, with funding from the U.S. President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief (PEPFAR), piloted the first two-way medical cargo drone flights between health facilities in Nkhata Bay and seven other hard-to-reach places like Thotho. The goal of the supply chain project is to transport medicine, diagnostic samples, and test results between the facility and the processing hospital much more quickly.

Rapid sample turnaround helps doctors to diagnose patients faster, resulting in more effective treatment. For instance, to make sure patients receive proper therapeutic regimens, antiretroviral therapy should only begin once a diagnosis is made based on test results from blood samples. A patient already on antiretroviral therapy and not responding well to treatment may learn from their test results that they require a different treatment regimen altogether.

Before the drone program, the roundtrip transport of health supplies to and from health facilities in the area could take up to two months, delaying diagnosis and treatment. And even then, some patients’ test results never reached health facilities because samples or results were lost in transit.

Often, Baxton had to use his own money to travel by boat down the coast to buy the medicine Thotho needed, spending the night before returning to his village. Doing so robbed him of valuable time serving patients.

Since the initial flight in July 2019, the drones covered 12,250 miles during 428 flights carrying medicines, medical supplies, lab samples, test results, and associated documentation. Reducing chain of custody handoffs also reduced the risk of damage or loss. While using the drones, the number of lost or damaged testing samples fell from 40 percent to essentially zero.

“The drone and my work are friends now,” said Baxton, “because if I say I don’t have drugs, my colleagues send drugs by drone.”

Drones are one of many new approaches the U.S. government is exploring to improve service delivery and to position health products and services closer and make them more accessible to the patients that need them.

This project shows the promise of integrating drones into health supply chains to reach remote locations across the globe.

By also using a vendor who not only provided the drone itself, but professional expertise through a pilot and ground operators, quick ramp up of the activity was possible. Likewise, the vendor provided regular maintenance and troubleshooting of the drone, allowing for quick upgrades to products as they became available. Similarly, this service-level approach meant short-term activities could quickly commence without requiring a long-term commitment and a significant initial capital investment.

Because of the length of the activity, which lasted several months longer than previous demonstrations of bidirectional health deliveries in Africa, the project also captured valuable information on implementation challenges and opportunities when operating for an extended period. Long-term viability for the future of drones in health supply chains will depend on solid country government buy-in and ownership, as well as adequate resources, coordination, and planning. Taken together drones can play a critical role in ensuring the viability of country supply chains thereby improving the health of citizens.

Back in Thotho, the village’s tranquility is rarely broken except in the early and late-night hours when the fishermen beat their drum cadence. All this changes when the drone lands as dozens of children pour from the cliffs, breathing life onto the beaches, clamoring for a glimpse under the watchful eyes of their mothers curing fish along the shore.

Comment

Make a general inquiry or suggest an improvement.