Speeches Shim

Spreading Media Literacy in Central Asia

Like millions of people around the world, Bagila Akhatova has been working from home since March. Instead of lecturing from a university classroom, she now uses applications such as Teams, Quizlet, Jamboard, Padlet, and WhatsApp, and is available around the clock to her students virtually.

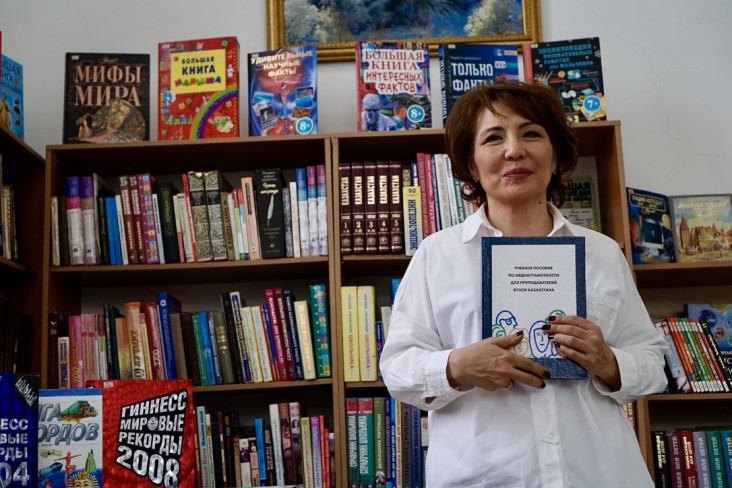

Bagila is a professor at the Kazakh Ablai Khan University of International Relations and World Languages. She teaches communications, public relations, and media studies to doctoral, master’s, and bachelor’s students. She is an established media literacy expert and is on the frontlines in the fight against the spread of disinformation in Central Asia.

It’s no surprise that she is always busy. The spread of disinformation has skyrocketed during the pandemic. Now more than ever, she feels a sense of duty to educate people of all ages about media literacy.

“Everyone needs to understand the importance of media literacy, from children to pensioners. It has such a significant impact on our society,” she says. “People need to be able to think critically and differentiate between fact and propaganda. Right now, sadly, many people fall for propaganda or believe fake news because they don’t fact check the information or source.”

A recurring example of the spread of disinformation during the pandemic is the story about airplanes dropping toxic substances over cities across Kazakhstan causing a rise in the number of COVID-19 cases. “What’s worse is media outlets are also sharing these stories because they are clickbait. The stories spread like wildfire. People then tend to believe these stories because they are seeing them across platforms,” says Bagila.

Bagila believes in encouraging citizens to critically assess media. “Media literacy is literacy of the 21st century. Everyone should be taught how to differentiate between fact and fiction and analyze information. I always recommend doubting information over blindly believing it. I ask people to consider, who created this message? Who benefits from the spread of this story? Go to the source and analyze if it’s credible. When in doubt, turn to fact-checking sites such as StopFake.kz, FactCheck.kz and Infodemiya.” These platforms are run by trained journalists.

In 2018–19, USAID through its Access to Information Program, partnered with international media experts — including Bagila — to create the Central Asia Media Literacy Manual in Russian. Through USAID’s Central Asia Media Program, implemented by Internews, the book is now available in Kazakh and Tajik languages, and will soon also be available in Uzbek language.

The media literacy manual is being used to teach media literacy courses across Kazakhstan and Tajikistan. The book is also available free of charge online on the NewReporter website supported by USAID. It is being utilized by Internews and its trainers for media literacy trainings, reaching people across the region.

“My sections of the book include examples from Kazakhstan. As authors, we wanted to ensure we used examples from the country and region to make the content relatable,” Bagila says. “We developed content keeping in mind our audience, using simple and easy-to-understand language and concepts that could be adopted by teachers and university professors.”

The manual includes some theory and a lot of practical exercises. “We were determined to make the content interactive and included lots of games and online resources so that participants are engaged and enjoy learning,” says Bagila.

Bagila herself has been using the manual in her media literacy classes for people across diverse age groups from young students to pensioners. To date, she has taught approximately 400 people about media literacy.

Nikos Marmalidi, a volunteer at the Kostanay American Corner, participated in a media literacy training in 2019. “As an active user of multimedia resources, I found the training extremely helpful both professionally and personally. Media literacy makes critical thinking possible. We now have a media literacy section on our Instagram page,” said Nikos.

Media literacy workshops are empowering citizens from all walks of life to be more savvy consumers of news and spread the need to fact-check sources of information before trusting the authenticity of a story.

The USAID-supported media literacy manual is being used in 21 of 23 universities in Kazakhstan that offer journalism and mass communications programs, and three universities in Tajikistan, reaching thousands of university students.

“I love what I do. Research, communicating with people, sharing my knowledge, it keeps me going. Nothing makes my day more than seeing my students have an aha moment when we’re discussing media literacy,” says a beaming Bagila.

Comment

Make a general inquiry or suggest an improvement.