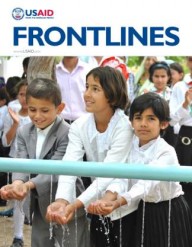

Girls in Jerash pose in front of their school’s storage tank that is painted to look like an aquarium.

Alysia Muller

Girls in Jerash pose in front of their school’s storage tank that is painted to look like an aquarium.

Alysia Muller

Girls in Jerash pose in front of their school’s storage tank that is painted to look like an aquarium.

Alysia Muller

Girls in Jerash pose in front of their school’s storage tank that is painted to look like an aquarium.

Alysia Muller

Speeches Shim

Zaatari village lies just south of Jordan’s border with Syria, where small villages are interspersed with livestock, olive farms, dairies and food factories. In 2009, Ahmed Al Khaldi received a $1,700, USAID-funded revolving loan from his village cooperative to install a 30-cubic-meter cistern to store rainwater harvested off his roof. The 51-year-old retired police officer knew it would give his family peace of mind during recurring periods of water scarcity.

Jordan is among the driest countries in the world. Rapid population growth has reduced the amount of fresh water available to the average Jordanian to less than 158 cubic meters per year—10 times less than the average U.S. citizen consumes. The renewable water supply—the water that is replenished each year by rainfall—only meets about half of total water consumption. The rest of the water used in Jordan comes primarily from aquifers that are slowly being depleted; alternative sources such as desalination are very expensive.

As is typical across the country, municipal water was delivered infrequently in Zaatari. If the storage tank ran out, the Al Khaldi family had to buy expensive truckloads of water from local businessmen. “With the cistern, I feel secure. Every time I need water, I just pump it from the cistern,” he says. “We can even share with neighbors if they run out of water.”

The cistern does not meet all the water needs of the Al Khaldi family. But it does provide important support for three generations of Al Khaldi’s immediate family—15 members in all—living under one roof.

Al Khaldi also couldn’t imagine that this cistern would eventually help him throw a lifeline to relatives living hundreds of kilometers away in Homs, Syria. Like many Jordanians in the north, his tribe lives on both sides of the border. In 2011, his Syrian cousin, Ahmad Swaidan, fled to Jordan with his wife and five children and his brother’s five children. “The shelling threatened our lives daily,” Swaidan says.

Like 200 other families in Zaatari, the Al Khaldis took in their Syrian relatives, housing them in an adjacent family property. By local estimates, the village’s Jordanian population of 8,000 had absorbed 2,000 Syrian refugees by November 2012. Al Khaldi says “it’s not easy” to support an additional 12 people on his monthly pension of $500 and the modest army salaries of his three sons—two of them married. “But we share,” he says.

1,500 Refugees a Day

Since 2006, the USAID-supported initiative to establish simple water-harvesting and conservation habits across Jordan has empowered rural families to take control of their water security. When conflict broke out in Syria in 2011, these communities were better prepared for what was coming. As conflict intensified in 2012, about 500 Syrian fled across the border daily. By the end of 2012, as many as 1,500 refugees a day were escaping into Jordan.

Water shortages in the area have intensified with the arrival of Syrians and the establishment of the 60,000-capacity refugee camp just outside Zaatari village. Thanks to the water-harvesting system, though, which pipes water down to the cistern at ground level, water supplies and expenses are manageable for the joint Al Khaldi-Swaidan household of 27 people.

“If we didn’t have the cistern, we would need to buy extra water four times a month at a total cost of JD 80 ($113),” Al Khaldi says. “Now it’s only twice a month.”

The same applies for 22 other Zaatari families who bought cisterns with USAID-backed loans.

The Al Khaldi family is also sharing their water-conservation habits with their Syrian relatives. “We never worried about water in Syria but now our family understands,” says Swaidan, a plumber, adding that he hopes to one day bring these practices back with him to Syria.

Along with the cistern, the Al Khaldi family started using some simple water-saving devices provided by the USAID project. On his own initiative, Al Khaldi installed a tube to divert dishwater from the kitchen out to the vegetable garden. “The family needs to wash and clean every day but we are more careful about how we use water,” says Al Khaldi.

The USAID-funded program, known formally as the Community-Based Initiative for Water Demand Management, is implemented by Mercy Corps, with its partners: the Jordan River Foundation, the Royal Scientific Society and 135 local community-based organizations throughout Jordan.

For the 23 Zaatari households that bought cisterns with USAID/Mercy Corps-funded loans, the terms require them to pay back $57 a month over 30 months. The Zaatari Cooperative Society, a local partner, reports a 100 percent on-time loan re-payment rate for every family. The project also provides grants to schools, community centers and other public buildings so they too can benefit from water collection and saving practices.

The project has also changed the ways households and communities understand, discuss and manage their water resources.

“People are now aware of Jordan’s water shortage, not only at the individual level but as a shared problem of the country,” says Ahmad Bani Ata, a Mercy Corps monitoring and evaluation manager.

Mohammed Bani Mustafa, a Mercy Corps supervisor, agrees that families involved in the water-management project develop a different attitude about their roles as citizens.

“People used to say that water is the government’s problem, but now they realize they have to know how to deal with water shortages, to take responsibility for their own households,” he says. “By delivering systems and technical support, we can help. But if they hadn’t changed their attitudes, it wouldn’t last.”

An unexpected benefit of the USAID project has been that the expertise developed during this project will be applied to future projects. Jordanians working for the NGO, members of the community-based organizations, and other residents have all learned a great deal about collecting and conserving water—knowledge they will pass on in their work and to their neighbors.

A recent $20 million grant from the U.S. Government’s Complex Crises Fund will build on this project’s efforts to assist Jordanians and an increasing number of refugees from Syria in the northern governorates meet their water needs. The experience in Zaatari and the Al Khaldi family will help thousands of other people in the north get the water their families need.

Comment

Make a general inquiry or suggest an improvement.