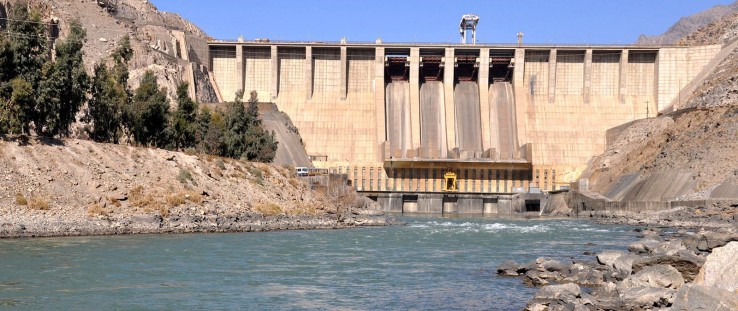

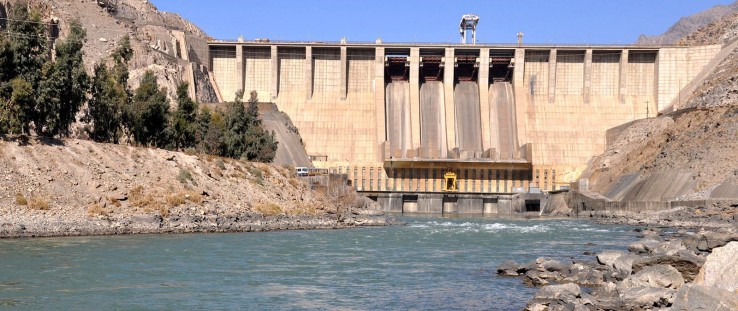

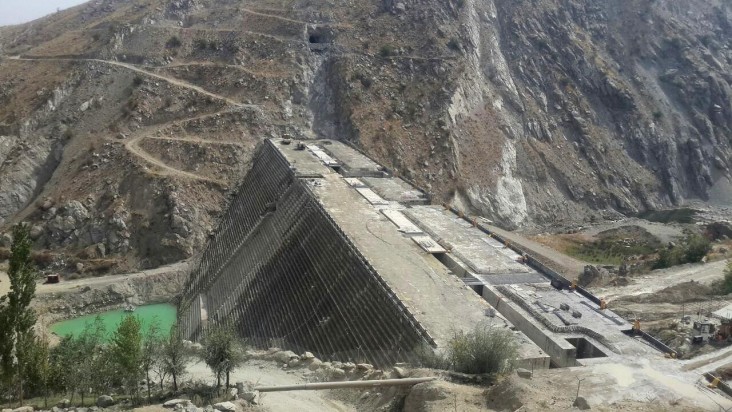

The Naghlu hydroelectric dam on the Kabul River supports the largest hydroelectric power station in Afghanistan.

ICIMOD

The Naghlu hydroelectric dam on the Kabul River supports the largest hydroelectric power station in Afghanistan.

ICIMOD

The Naghlu hydroelectric dam on the Kabul River supports the largest hydroelectric power station in Afghanistan.

ICIMOD

The Naghlu hydroelectric dam on the Kabul River supports the largest hydroelectric power station in Afghanistan.

ICIMOD

Speeches Shim

Like many sources of water all over the world, the Kabul River and its tributaries are at the center of a looming crisis—a limited supply of water and many people who depend on it to survive and prosper.

Fed by ice, snow and rain, the mighty Kabul River flows east out from the Hindu Kush Mountains of Afghanistan following the Grand Trunk Road through the Khyber Pass into Pakistan, where it joins the Indus River near the city of Attock. Along the way it passes the cities of Kabul and Jalalabad in Afghanistan and Peshawar and Nowshera in Pakistan.

In total, the Kabul River is the sole source of drinking water for almost 7 million people in both Afghanistan and Pakistan and contributes one-fourth of Afghanistan’s freshwater. Nearly 25 million people live in the basin, making the waterway a vital source of life and livelihood for a sizeable cross-border population. The total population of the basin is expected to increase to 37 million by 2050.

In Afghanistan, the river provides water to irrigate crops, and supplies 50 percent of the country’s hydropower. On the Pakistan side, the river powers the 250-megawatt Warsak Dam built in 1960, which generates 1,100 gigawatt hours of electricity per year and provides irrigation for the fertile Peshawar valley.

But there has been a challenge in this relationship: Communication is difficult. Both countries have critical needs that depend on the Kabul River, but there are no formal treaties or traditional mechanisms to discuss issues related to the water supply.

That is where Zhanay Sagintayev enters the mix.

He is one of several scientists supported by USAID’s Partnerships for Enhanced Engagement in Research (PEER) program, which uses NASA’s satellite imagery data to identify floods, determine surface water coverage, and observe droughts across the Kabul River Basin. The project began in late 2016.

With this data, research teams expect they will be able to create combined surface and groundwater models that can be used by water managers in both Afghanistan and Pakistan to better predict floods, droughts and improve water management decisions that impact millions of people.

Sagintayev, who goes by Jay Sagin, is collaborating with researchers from both Afghanistan and Pakistan through his laboratory at Nazarbayev University in Astana, Kazakhstan. Central Asia has a history of positive relations with neighboring countries, including Afghanistan and Pakistan, and often hosts regional meetings.

The Government of Kazakhstan has also played a role in the economic development of Afghanistan by supporting programs that train Afghan professionals. “We have many similarities in our culture, food, traditions; it is easy to communicate with Afghan and Pakistani researchers. They are our neighbors. We have to be in good relationship with our neighbors. Their success and difficulties influence on our country, Kazakhstan,” says Sagin.

Sagin’s partners include Mohammad Najaf from Kabul Polytechnic University and Muhammad Abid from the COMSATS Institute of Information Technology (CIIT) in Pakistan. The trio is working with the NASA data. Sagin’s project is also training Afghan and Pakistani water researchers to use remote imagery, including a recent training attended by 21 students, researchers and government professionals from both countries and supported by the Regional Research Network “Water in Central Asia” program. According to Sagin, efforts like these are crucial for future cooperation in both Central Asia and the Kabul River Basin.

Scientists Speak the Same Language

The idea of science as a means of promoting cooperation is not new. Sharing scientific information has been critical to the success of the nearly 60-year-old Indus Waters Treaty between India and Pakistan. “It is ... easier to communicate among scientists as they technically speak the same language,” says Azeem Shah of the International Water Management Institute (IWMI).

Based in Colombo, Sri Lanka, with offices in 11 countries across Africa and Asia, IWMI uses science and technology to address sustainable water and land use problems in partnership with governments, civil society and the private sector.

Along with the World Bank and the International Center for Integrated Mountain Development, IWMI supports the Indus Basin Knowledge Forum, a series of meetings that bring together government representatives and researchers from Afghanistan, China, India and Pakistan to share knowledge and foster cooperation.

Before working on the Kabul River, Shah’s research focused on broader water issues impacting India and Pakistan, so he understands the importance of information when it comes to transboundary cooperation. “I realized there is little scientific evidence available to determine how climate change will impact the flows of Kabul River along with the human interventions that are taking place .... This was the main motivation which prompted me to investigate this important issue,” says Shah.

Shah is creating hydrological and rainfall models of the Kabul River Basin to determine future water availability. In order to make accurate models, he needed a partner in Afghanistan to gather data.

In the beginning, he says, “It was quite a task to find people from Afghanistan with relevant expertise in the area of hydrology to contribute in this research project.”

But through IWMI’s engagement work in the region, he was eventually connected with Wasim Iqbal. Meeting Iqbal, an adviser to the Afghan Ministry of Energy and Water, was the key to building models that represent the whole Kabul River Basin. “We extended our willingness to engage him and thereafter it has been a great collaborative experience so far,” says Shah.

In addition to developing models, Shah is leading IWMI’s effort to create the Kabul River Basin Knowledge Platform, an online open source platform that will serve as a single source of knowledge for any scientific material that is available on the Kabul River Basin.

With this tool, researchers from both Afghanistan and Pakistan will be able to collaborate and share information, slowly breaking down barriers that can help build a platform for broader confidence-building discussions between countries in the region, including measures toward lasting political cooperation.

Promising Early Results

These scientific collaborations are already producing valuable data. Sagin and his colleagues have identified significant reductions in glaciers within the Kabul River Basin. Sagin and his team are taking ground measurements to calibrate their models and precisely measure glacier reductions. The new data is informing major infrastructure projects, including a municipal water purification and reuse project in Kabul City.

Early results of Shah’s models show that peak river flows will decrease over 5 percent by 2100 and that flood frequencies in Pakistan will also decrease. Shah will be refining these models with data obtained from colleagues in Afghanistan and creating visualizations of different water use and climate scenarios.

Jason Porter is a research adviser with Apprio, Inc.

Comment

Make a general inquiry or suggest an improvement.