Left to right: Veronika Shivute, Rightwell Zulu and Felistas Shindimba work together to improve early HIV diagnosis for infants so those who test positive can start treatment as soon as possible and those who test negative can stay HIV-free.

Sheena Sharifi, USAID

Left to right: Veronika Shivute, Rightwell Zulu and Felistas Shindimba work together to improve early HIV diagnosis for infants so those who test positive can start treatment as soon as possible and those who test negative can stay HIV-free.

Sheena Sharifi, USAID

Left to right: Veronika Shivute, Rightwell Zulu and Felistas Shindimba work together to improve early HIV diagnosis for infants so those who test positive can start treatment as soon as possible and those who test negative can stay HIV-free.

Sheena Sharifi, USAID

Left to right: Veronika Shivute, Rightwell Zulu and Felistas Shindimba work together to improve early HIV diagnosis for infants so those who test positive can start treatment as soon as possible and those who test negative can stay HIV-free.

Sheena Sharifi, USAID

Speeches Shim

Squinting in the hot northern Namibian sun, a man smartly dressed in a nurse’s uniform greets us with a warm smile. Rightwell Zulu, or “Dr. Zulu,” as he is affectionately called by his colleagues, is a nurse mentor at Nyangana District Hospital in Namibia.

Zulu, together with his colleagues, Veronika Shivute and Felistas Shindimba, developed a system that has helped this hospital test nearly every baby born there to HIV-positive mothers. Their work is supported by IntraHealth International and USAID/Namibia through the U.S. President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief.

In Namibia, HIV prevalence is highest in the northern regions, including Kavango East, which has the third-highest HIV prevalence rate in the country. The Nyangana District Hospital provides basic health services to over 38,000 Namibians in Kavango East, including HIV testing, counseling and treatment. The hospital is known for its busy maternity ward, and is the sole facility in Nyangana equipped to carry out deliveries.

An important goal for hospital staff is to determine how many HIV-exposed babies are in the district and how many of them are being tested. A baby can contract HIV while a mother is still pregnant, or after birth through breastfeeding, making early infant diagnosis critical.

Zulu and his team developed a detailed procedure that ensures close coordination among the hospital’s nurses and health assistants, outreach clinic staff and community health workers. The system tracks HIV-positive mothers and ensures their babies are tested at six weeks, nine months and 18 months. As a reminder, prior to each time interval, the team calls each mother, confirming the appointment.

Zulu and his team aim to start HIV-positive babies on treatment as soon as possible, and keep HIV-negative babies HIV-free.

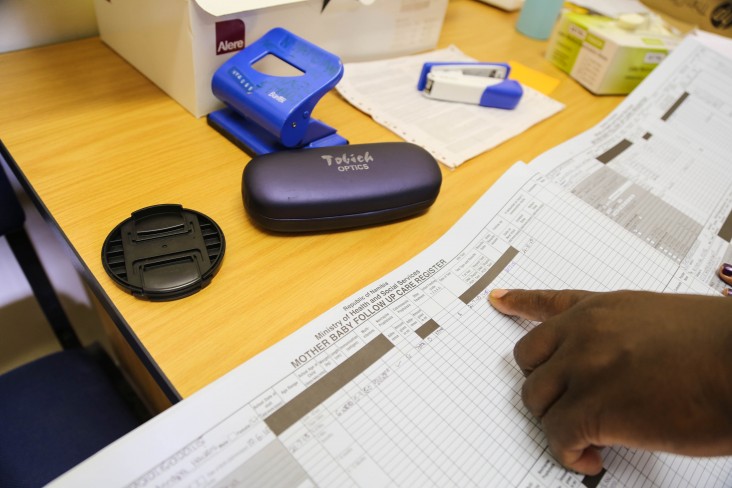

Shindimba, who is the district’s monitoring and evaluation officer, makes monthly visits to outreach clinics.

“Sometimes you see that mothers are missing,” Shindimba says. “For example, we might have referred a mother to a certain clinic for her first baby follow-up on Dec. 6. When we go at the end of December to check the appointment registers, we might see that the mother did not come on her assigned day to that clinic.”

When this happens, Shindimba calls the mother. In cases where mothers cannot be reached by phone, she shares the list with community health workers. They are in charge of connecting with mothers at their homes or in their villages, and coordinating with outreach clinics to ensure mothers reschedule their baby’s follow-up visit for HIV testing. Shindimba also uses the monthly visits to collect data on HIV-exposed infants.

At first, there were many gaps in data. However, by improving regular communication with mothers, outreach clinic staff and community health workers, Zulu and Shindimba feel that data quality has greatly improved, and they are able to adequately trace HIV-exposed infants in Nyangana.

Within the last year, three babies in the Nyangana district were born HIV-positive, all of whom are currently on treatment. Between the start of the tracking system in October 2015 and June 2016, Zulu and his team increased rates of early infant testing from 29.3 percent to 94.4 percent of all the babies born in Nyangana to HIV-positive mothers. That’s nearly 100 percent—a goal the team believes it will eventually reach.

Their patients are taking note.

“With support, encouragement and health education, I’m reminded to take my baby for the required HIV test and administration of HIV medications to prevent my baby being infected since I am a HIV-positive mother. I learned that it’s possible to be HIV-positive and have a HIV-negative child,” says Kamonga Eveline, one mother who has benefited from the improved early infant diagnosis system.

Mashika Elizabeth, another mother, shares that improved communication with the hospital and clinic staff serves as a reminder and encouragement to take her baby for HIV tests on time and breastfeed while taking antiretroviral medications.

“I take my medication on time every day to ensure my baby does not get infected. I believe this is the benefit for the nation because it prevents new infections from mothers to babies,” she told us.

While their system has been largely successful, some challenges still exist. Phone numbers change or become unreachable. Mothers transfer to different clinics without notification. Regardless of the challenges, Zulu and his team continue to work hard to improve their tracking system.

“This project is my baby, and we still want to see how we can improve this system,” Zulu says. “The issue for me now is that innocent children are still getting HIV. This is what I care about. When you see a child who tests positive, then we pause. The programs are there, but something is still not working.”

Valery Mwashekele and Cherizaan Willemse of IntraHealth International contributed to this story.

Comment

Make a general inquiry or suggest an improvement.