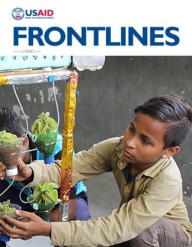

A teacher helps students perform a science experiment at Kavi Kalidas Primary School.

Neha Khator, USAID

A teacher helps students perform a science experiment at Kavi Kalidas Primary School.

Neha Khator, USAID

A teacher helps students perform a science experiment at Kavi Kalidas Primary School.

Neha Khator, USAID

A teacher helps students perform a science experiment at Kavi Kalidas Primary School.

Neha Khator, USAID

Speeches Shim

Located in a quiet corner in the impeccably clean city of Surat in the state of Gujarat is the Sant Pujya Shri Mota Primary School. Dharmiben Patel is the school’s headmaster—but she is no ordinary principal.

Dressed in a neatly draped floral print sari with hair tied back in a sleek ponytail, 30-year-old Patel is possibly one of India’s youngest headmasters. A former lecturer in a local college, Patel became the headmistress after passing a government-appointed test. It was when she switched roles that Patel saw India’s deep education crisis firsthand.

According to the largest non-government household survey in India, over 50 percent of fifth grade children in India are not able to read second grade-level texts, and only 26 percent can perform division. In Patel’s school, these grim statistics held true.

Out of a total 34 students in fifth grade, only 27 percent grasped mathematical concepts while fewer than 25 percent could read.

Most reports in India blame poor reading abilities on a lack of quality teachers and their erratic attendance, but Patel disagrees.

“Most children in public schools belong to socially and economically weaker sections of the society. As a result, they are often called to work by their parents during school hours or are simply not motivated to study. Moreover, every week, the government summons the teachers for various non-teaching duties that compromise our ability to deliver any meaningful lessons,” she says. “There were days initially when I just wanted to quit and return to college. But then I decided to stay and fight.”

And in July 2015, Patel found the means to fight under the USAID-supported School Excellence Program.

USAID, in partnership with the Kaivalya Education Foundation, began the program in October 2014 to transform Surat’s 258 poor performing primary education public schools by developing leadership and teaching skills of three key agents of the public education system: teachers, headmasters and district-level school officials.

Under the program, Kaivalya and its cadre of 64 Gandhi Fellows (young postgraduates from India’s premier colleges) began training 258 headmasters and 1,800 teachers to improve the reading abilities of more than 150,000 children. Patel, too, received training on better school management practices such as reforming school management committees and morning assemblies, introducing games in classrooms, and forming child parliaments.

A firm believer in the power of change, Patel quickly adopted the new methods introduced under the program.

“She began use of instruments, song and dance in the morning assemblies, started elocution competitions, increased the use of storytelling in classrooms, and street play performances by students. In fact, she even composes songs and stories that she can use in her lessons,” says 25-year-old Dipti Hajari, a Gandhi Fellow who holds a master’s in social work and found it exciting to work with Patel. “Being young and almost the same age as me also made it easy.”

To Patel’s surprise, the new methods yielded quick results: There has been a 152 percent increase among fifth grade students’ reading and comprehension skills while math performance has increased 159 percent. “It was also amazing to see how many school talents emerged during these playful exercises,” she said, adding that the students’ newfound confidence is translating into better thinking and learning.

“It was never a struggle to teach college students because they have better attention spans and can grasp lessons quickly. But I have unlearnt all that. In this school, I’m a learner myself. It’s all about going back to the basics,” says Patel.

Ready, Set, Learn

Meanwhile, across town in Kavi Kalidas Primary School, fourth grade student Shivam Pandey has been holding a flash card for 15 minutes and is now getting desperate. “When will he call me?” he whispers, as his little hand remains suspended in the air, ready to launch at the first call.

After waiting for another two minutes, the teacher finally calls out for the letter “B.”

“Sir! Me!” shouts Shivam, throwing his hand up in the air at lightning speed.

“Come” signals the teacher as he calls two more students forward, each holding flash cards with a different letter. The teacher then asks a fourth child to come rearrange the flash cards to make a word.

After pausing for a few seconds, the fourth student succeeds in forming a word and the class bursts into rhythmic applause for their classmate’s correct answer. The teacher, Raj Kumar, gleaming with joy, asks the students to return to their seats to let another batch of three students with flash cards take their place.

“Not only did the fourth student make the right word, I’m happy that everyone in the class knew that he made the right word,” he says.

It has been over a year and a half now since Kumar joined the School Excellence Program. Every week, Kumar sits with Sanchita Sarkar, his Gandhi Fellow, to carefully plan each lesson, making them as interactive as possible. “I have started using storytelling, flash cards, poster- and model-making, music, singing and dancing in my classroom. My only motto is to make kids as involved in learning as possible,” he says.

As part of the USAID program, Sarkar recently videoed a lesson that Kumar delivered to help him further improve his teaching skills. Developed by the New York University, the Teachers Instructional Practices and Processes System (TIPPS) tool is a technique designed to improve teaching performance by observing videos of classroom instruction. The videos are analyzed against 19 indicators such as whether the teacher is attentive, involves the entire classroom, and favors brighter students. Based on the analysis, the program provides recommendations for teachers to work on their weaker points.

“In many schools we have had instances where teachers have greatly benefited from the tool’s analysis. Many now even record their own videos and bring it to us asking how can they improve their classroom instruction,” says Sarkar.

The Teacher Becomes the Student

One such teacher is 54-year-old Jayshree Kopershinde at Sant Gadge Baba Primary School in Surat. After Kopershinde saw her classroom video, she realized why most of her students struggled to even form sentences—her dry-as-dust lectures were failing to stimulate the young minds.

“Jayshree focused too much on rote memorization and finishing the syllabus. While she wrote on the board, the kids would laugh behind her back. Some even scribbled in their books without paying attention to what she was writing on the board,” says Anand Baraik, another Gandhi Fellow.

Following the startling discoveries in the video, Kopershinde decided to rearrange the class seating, grouping students into teams of four, each with three weak students and one bright student.

“She began telling jokes in the classroom to help students engage with her. She would use newspaper advertisements and movie posters to organize reading comprehension competitions,” says Baraik.

Kopershinde was also the first teacher in her school to use a smartboard to deliver lessons. Provided by the state education department, the smartboard was, until a year ago, gathering dust in the school’s storeroom.

“She would get informational videos on her mobile to show to her class. After the video, she would read chapters from the syllabus that helped students remember the lessons better. She even downloads videos, songs and quiz competitions online using the smartboard,” Baraik said smiling. “She is getting more and more innovative in her teaching—even more than what we had trained her in the workshops!”

A teacher with over 30 years of experience, Kopershinde first found it difficult to believe that she had been doing it wrong all these years. “But I realized that to be able to accept criticism and learn new things is what makes you a good teacher. After I adopted these new methods, even the quietest girl in my classroom has turned into a chatterbox,” she laughs.

Comment

Make a general inquiry or suggest an improvement.