Speeches Shim

A recent study commissioned by USAID demonstrates that investing in a more proactive response to avert humanitarian crises could reduce the cost to international donors by 30%, whilst also protecting billions of dollars of income and assets for those most affected.

The Economics of Resilience to Drought - Infographic ![]() (pdf - 1 MB)

(pdf - 1 MB)

Humanitarian aid is critical for saving lives, alleviating suffering, and maintaining human dignity. However, aid often arrives late, and there is increasing recognition that this type of response is costly and unsustainable. Responding earlier saves lives, livelihoods and money. Investing in people’s resilience – their ability to manage shocks and stresses without compromising their future well-being – is also critical for reducing these humanitarian costs.

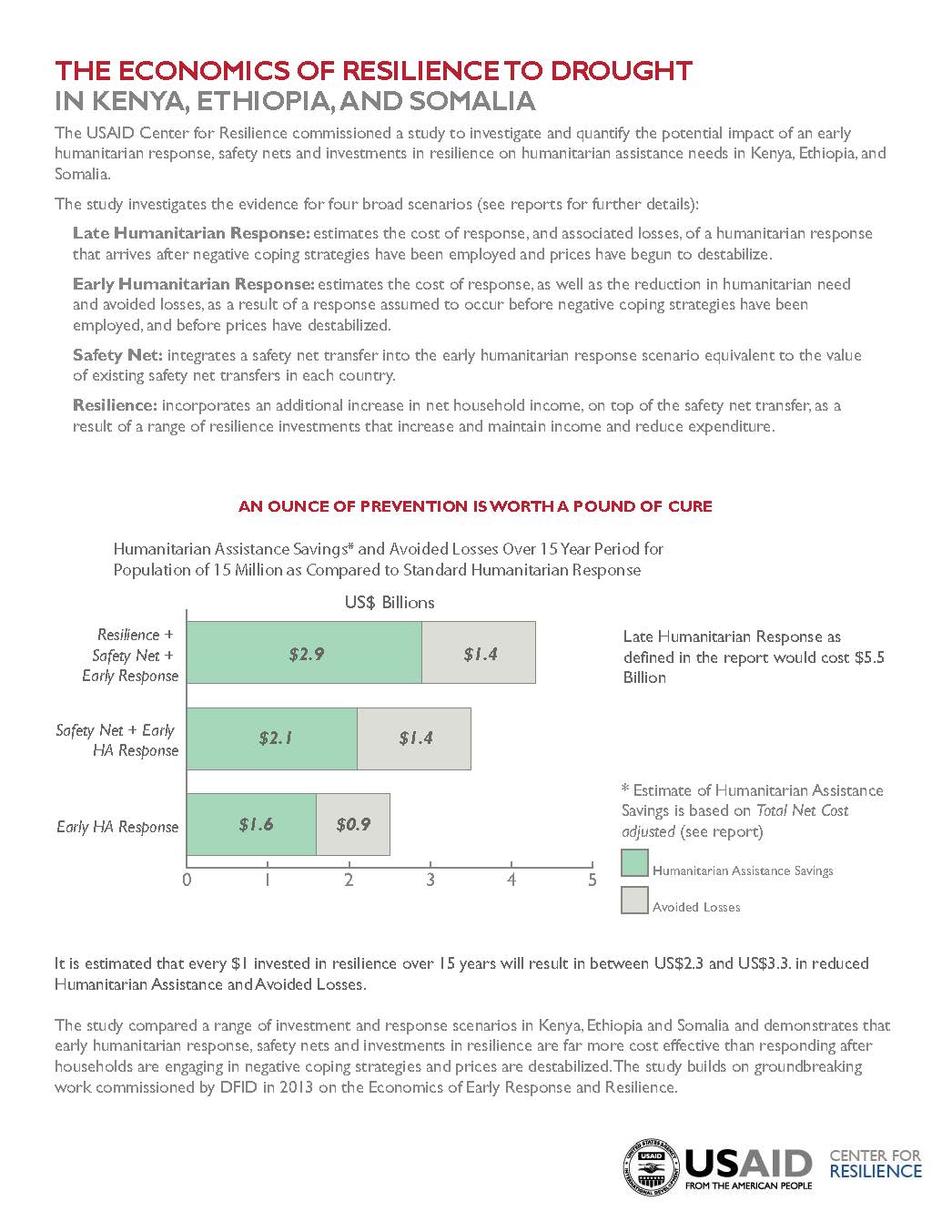

A recent study commissioned by USAID assessed the cost savings that could result from an earlier and more proactive response to drought in Kenya, Ethiopia and Somalia. The study finds that donors could save 30% on humanitarian aid spending through an earlier and more proactive response; this is equivalent to savings of US$1.6 billion when applied to U.S. Government spending over the last 15 years in these three countries alone. A more proactive response that can help to protect people’s income and assets is even more cost effective and can help households to manage the effects of shocks. When these benefits are incorporated, the overall savings increase to US$4.2 billion. Put another way, every US$1 invested in building people’s resilience will result in up to US$3 in reduced humanitarian aid and avoided losses.

These results are clear; investing in early response and resilience is significantly more cost effective than providing ongoing humanitarian aid. Investing in resilience is a win-win – it not only reduces human suffering, but it also reduces the cost to donors, allowing humanitarian aid dollars to go further and help more people. An ounce of prevention is worth a pound of cure.. This study evaluates the economic case for early response and resilience building in Kenya, Ethiopia and Somalia.

This series of studies involved extensive collaboration across a range of actors, and we would like to acknowledge their contribution.

The HEA modelling that fundamentally underpins this work was conducted by Mark Lawrence at the Food Economy Group (FEG), without whom this work would not have been possible. Tanya Boudreau at FEG provided input throughout. HEA baseline data was generously provided by the Government of Ethiopia, Mercy Corps International, Save the Children US/UK, Adeso and ACTED (STREAM Consortium), FSNAU/FEWS NET. FEWSNET and USGS provide the monitoring data used in the study.

We also wish to acknowledge the USAID country offices that supported this project, the Government of Kenya, FAO, WFP, and UNICEF for providing relevant data. Also all those who reviewed early drafts, including Adrian Cullis (Independent Consultant), Malcolm Ridout (DFID), Catherine Fitzgibbon (independent consultant), Peter Hailey (Center for Humanitarian Change); Dan Maxwell (Tufts – Feinstein International Center); Seb Fouquet (DFID Somalia); Dorian LaGuardia (Third Reef Solutions); Ric Goodman (DAI); Dustin Caniglia (Concern); Amin Malik and Danvers Omolo (FAO Somalia); and Utz Johann Pape, Philip Randolph Wollburg, Gonzalo Nunez, Ambika Sharma, and Manaal Fatima Ebrahim (World Bank).

Economics of Resilience to Drought: Executive Summary

Economics of Resilience to Drought: Summary of Overall Findings

Economics of Resilience to Drought: Ethiopia Analysis

Economics of Resilience to Drought: Kenya Analysis

Economics of Resilience to Drought: Somalia Analysis

Comment

Make a general inquiry or suggest an improvement.