- Work With USAID

- How to Work with USAID

- Organizations That Work With USAID

- Find a Funding Opportunity

- Resources for Partners

- Careers

- Get Involved

Speeches Shim

Background

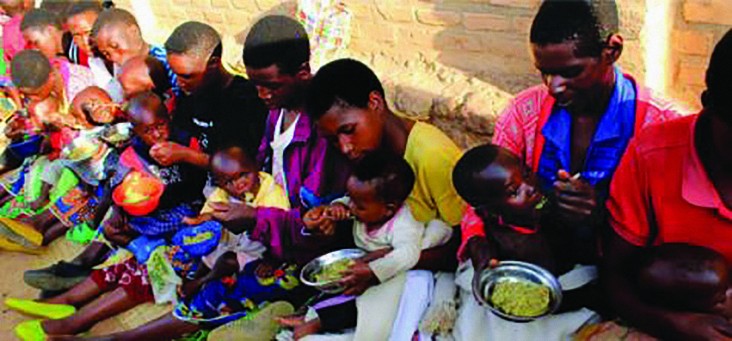

The “Tangiraneza/Start Well” project aimed to enhance the capacity of Ministry of Health (MOH) staff and Community Health Workers (CHWs) to implement impactful maternal, newborn, and child health interventions at the community level.

Project activities included: training MOH staff, CHWs, and local leaders in Integrated Care Groups (ICGs) for interventions in nutrition, maternal and newborn care, diarrhea, and pneumonia; monthly meetings of CHWs, religious leaders and community representatives to make action plans, coordinate regular home visits, and improve referrals; monthly home visits and community meetings led by ICG members to teach health/nutrition interventions and convey Behavior Change messages; mobilization of churches to assist vulnerable households with kitchen gardens and tippy taps (a hand washing device); implementation of supple-mentary Nutrition Weeks9 training in the Kaduha catchment area and the Rwandan MOH Community Based Nutrition Protocol (CBNP) in all areas.

There were 536 Integrated Care Groups (ICGs), one in each village; each ICG consisted of 10 members, including three community health workers, the head of the village, a religious leader, three village leaders in charge of social affairs, information and community development, the women’s leader, and a representa-tive of the hygiene club. Each member visited 10 homes on a monthly basis to educate on topics including nutrition, newborn care, diarrhea, and pneumonia, and to follow up.

Faith-Based and Community Initiatives

As an example of the project’s engagement with local leaders, 589 religious leaders, from thirteen church denominations, were involved in total, made up of 536 local religious leaders involved in each ICGs, and 53 senior religious leaders operating across the district. The inclusion of religious leaders in the ICG was emphasized to create and enhance trust between communities and health systems, and to endorse and triangulate health information during their household visits or at church. The role of religious and commu-nity representatives in the ICG was to share health messages with their networks and to help mobilize communities to take steps towards healthy behavior, including building latrines and improving kitchen gardens. Local religious and community leaders were also charged with making plans with their congregations for reinforcing key health messages and implementing three activities or outreaches annually to help the most vulnerable families follow healthy behaviors. For example, during the rollout of messages on hand washing, community members could be challenged to identify and support families for whom building a tippy tap might be out of reach—with the expectation that assistance be based on need regardless of religious affiliation.

Local leaders also participated in the evaluation functions in the project, regularly reporting the uptake of health and nutrition practices in their communities. They participated directly as enumerators during project evaluations, as well as in mobilization and sensitization of community participants in evaluation activities.

Results

Overall, the probability of achieving the Minimum Acceptable Diet (MAD) was 23 percent greater when a child had been involved in Nutrition Weeks. Minimum Dietary Diversity (MDD) more than doubled in the intervention area from the beginning to the end.

At the end of the project, a survey measured home visits by ICGs and delivery of health messages by churches. In Kaduha, 60 percent of respondents reported having an ICG member visit in the last month, and 39 percent reported receiving health information from a church, with respondents in Kigeme reporting 38 percent and 29 percent, respec-tively. With respect to religious groups, the project reported outcomes including an increased number of households reporting CHW, ICG member and church member visits; and that churches were mobilized to assist vulnerable families with kitchen gardens, tippy taps and small livestock.

A pastor in Mushubi Sector said, “As religious leaders, we should encourage self-reliance on available resources to be able to react quickly to certain health priorities.”

During focus group discussions, Kigeme and Kaduha Hospital Directors, Nutritionists, and Community Health Supervisors agreed that religious leaders played a critical role since they were trusted by their community and able to understand local needs.

Conclusion

The Care Group model was originated by World Relief in Mozambique. 23 NGOs have expanded in 27 countries. The Care Group model’s volunteers reached 10–15 neighboring households, delivering behavior change communication and community-based information systems. Cost is approximately $3–$7 per beneficiary per year, and the cost per disability adjusted life year (DALY) averted is $15–$126.

The Care Group model has evolved in Rwanda—community health care initiatives can now be tactically integrated within the health system architecture, beyond achievements of short term project goals and objectives. In Rwanda’s complex and evolving environment, health care organizations need to creatively innovate to ensure a resilient and responsive service delivery system that meets the needs and expectations of its people.

Comment

Make a general inquiry or suggest an improvement.